Hey you bastards, I’m still here!: Steve McGueen in Papillon, 1973

The other day I drove to Cedar Key to, um, commune with Michael Presley Bobbitt.

The one time Gainesville playwright (with two off-Broadway productions) turned Cedar Key “Clambassador” and last-survivors-on-the-island apocolyptic novelist (about which you will surely be hearing more at a later date).

Bobbitt has five two acre leases on which he raises thousands of clams. But he earned his Clambassador title through his relentless boosterism of the island and its growing aquaculture industry (clams, oysters, crabs).

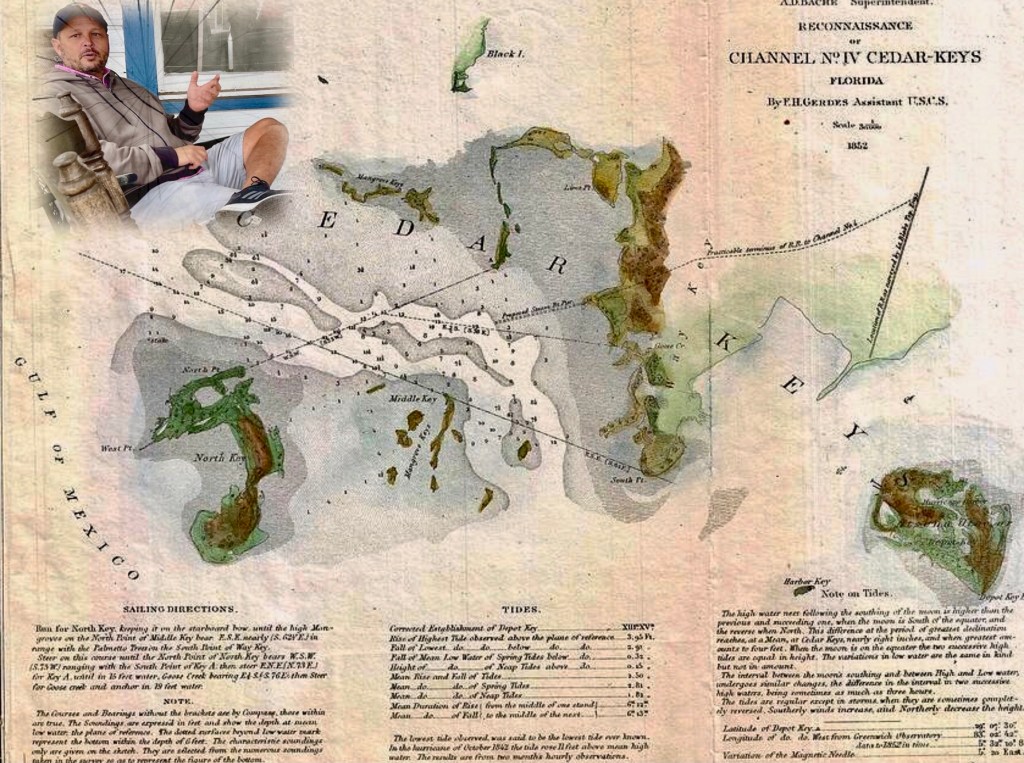

Apalachicola’s famed oyster industry has long since faded out. Cedar Key is just getting started.

Bobbitt fell in love with Cedar Key years ago when he was earning his pilot’s license. He would come to this spit of land on the edge of the Gulf to practice short takeoffs and landings on CK’s notoriously, um, unforgiving air strip.

But Bobbitt didn’t decamp from artsy GNV until after his marriage fell apart and he found himself in desperate need of a fresh start.

Polk County born and bred he may be. But Bobbitt has reclaimed his soul in Levy County’s Cedar Key.

(Fun fact: The great American Naturalist John Muir once walked from Fernandina to Cedar Key following railroad tracks. Once he got there he almost died from either yellow fever or malaria. I forget which.)

(The other fun fact is that while Muir was walking through what is now GNV he saw a naked man standing on a porch. Which seemed oddly appropriate to Hogtown.)

Seriously, you can’t make that sort of stuff up.

But I digress.

The point is that Bobbitt calls Cedar Key the “anti-Siesta Key.”

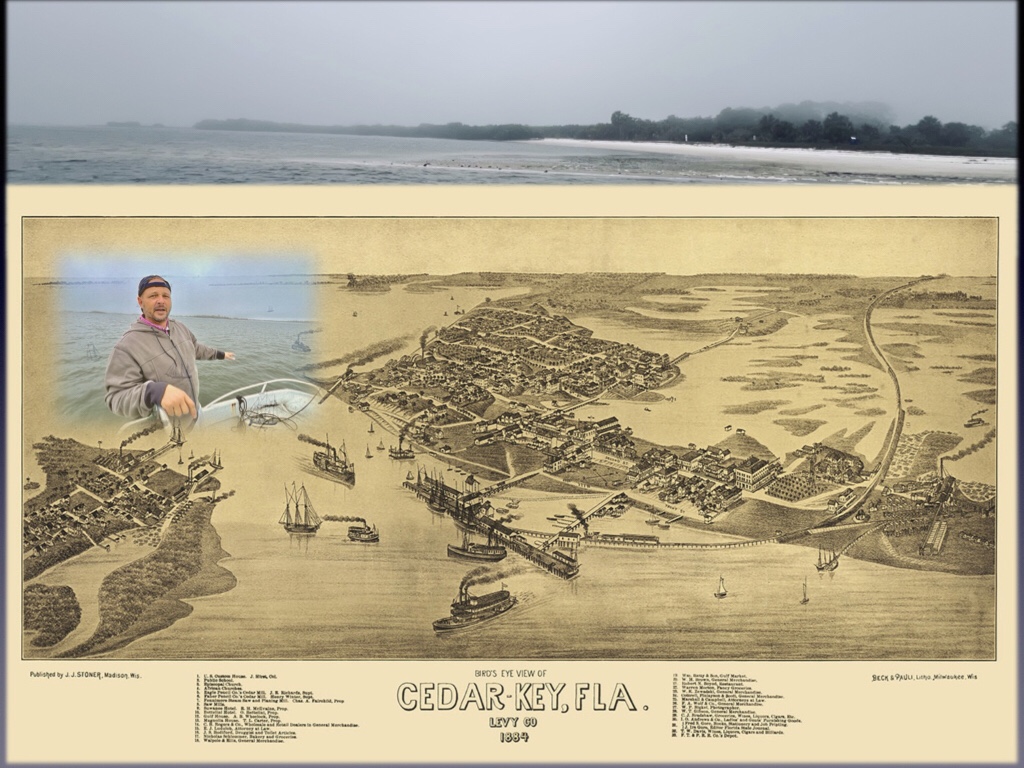

Simply not ready for prime time. “An Island Lost In Time.”

A town so determined to hang onto its blue collar, rough around the edges underpinnings that the locals imposed moratoriums on exactly the sort of condo commando developments that have laid waste to so many other erstwhile Florida fishing towns.

Oh, and Bobbitt once wrote a play called “Cedar Key.”

About that time a local blue collar, rough around the edges, underachiever saved the town by rowing out into the Gulf to persuade a raging hurricane to please go somewhere else.

Because you can do that sort of thing in a play.

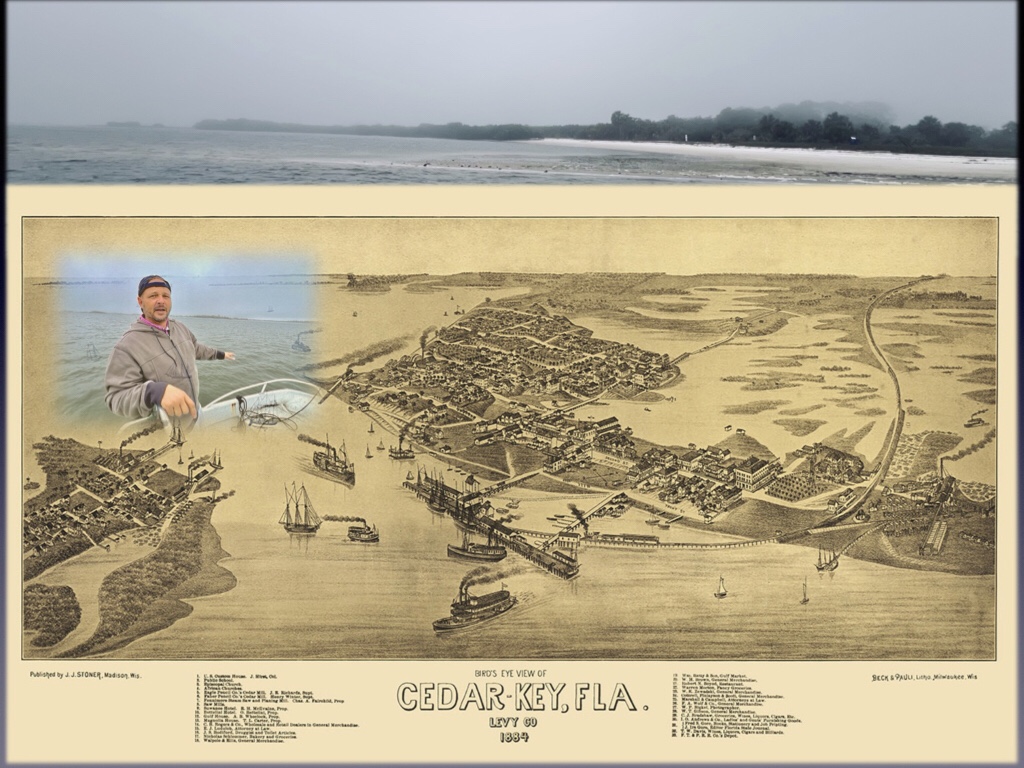

I only bring that up because, when Hurricane Idalia came calling, Bobbitt – perhaps realizing that rowing out and trying to reason with a freak of nature was a, um, fool’s errand – chose quite a different tack.

While other residents were battening their hatches or abandoning ship (as it were) Bobbitt braved the winds and rising waters to shoot video footage of the destruction. The timely sharing of which earned him media exposure around the world.

Dudes, I’ve been a journalist for 50 years, and I’ve never made the BBC.

Plus Bobbitt got to pal around with Jim Cantore while showing him Cedar Key’s decidedly soggy remains.

Idalia came and went. Some things got flooded. Some things got destroyed. They had to write city hall off as a loss.

But these days Bobbitt sits on the front porch of his restored circa 1840 house and brags about Cedar Key’s resiliency. (He also has a house boat that used to be a meth lab, but that, as the playwrights say, is another story entire.)

Listen, Idalia wasn’t Cedar Key’s first rodeo. Far from it.

Cedar Key has been there and done that. And done it again. And will almost certainly do it again.

Which, when you think of it, is just the town’s way of saying: Hey you bastards! We’re still here!

And who could argue with that? Certainly not Michael Presley Bobbitt.