My friend Shelley Fraser Mickle has written a lively biography of Alice Lee Roosevelt. I wrote this piece about her latest book for the current issue of Our Town magazine. Enjoy.

I can run the country or I can control Alice. I can’t possibly do both. Theodore Roosevelt

T.R. called Alice a “guttersnipe” after a boy dressed as a girl came knocking one day.

Told she couldn’t smoke in the White House, Alice defiantly puffed away on the roof.

She was known to carry a dagger in her purse and a tiny flask tucked into her glove.

Oh, and she helped stop a war – and win her father a Nobel Peace Prize – by mounting an international charm offensive.

For all her celebrity however, Alice Roosevelt never realized her most heartfelt desire: The unconditional love of her famous but emotionally distant father.

“We talk a lot in our culture about fathers and sons but never really have a conversation about what fathers give to daughters,” says author Shelley Fraser Mickle.

Mickle, who lives on a horse farm near Jonesville, has published more than a dozen novels and children’s books since 1989. But it has only been in the last few years that she turned to writing serious non-fiction.

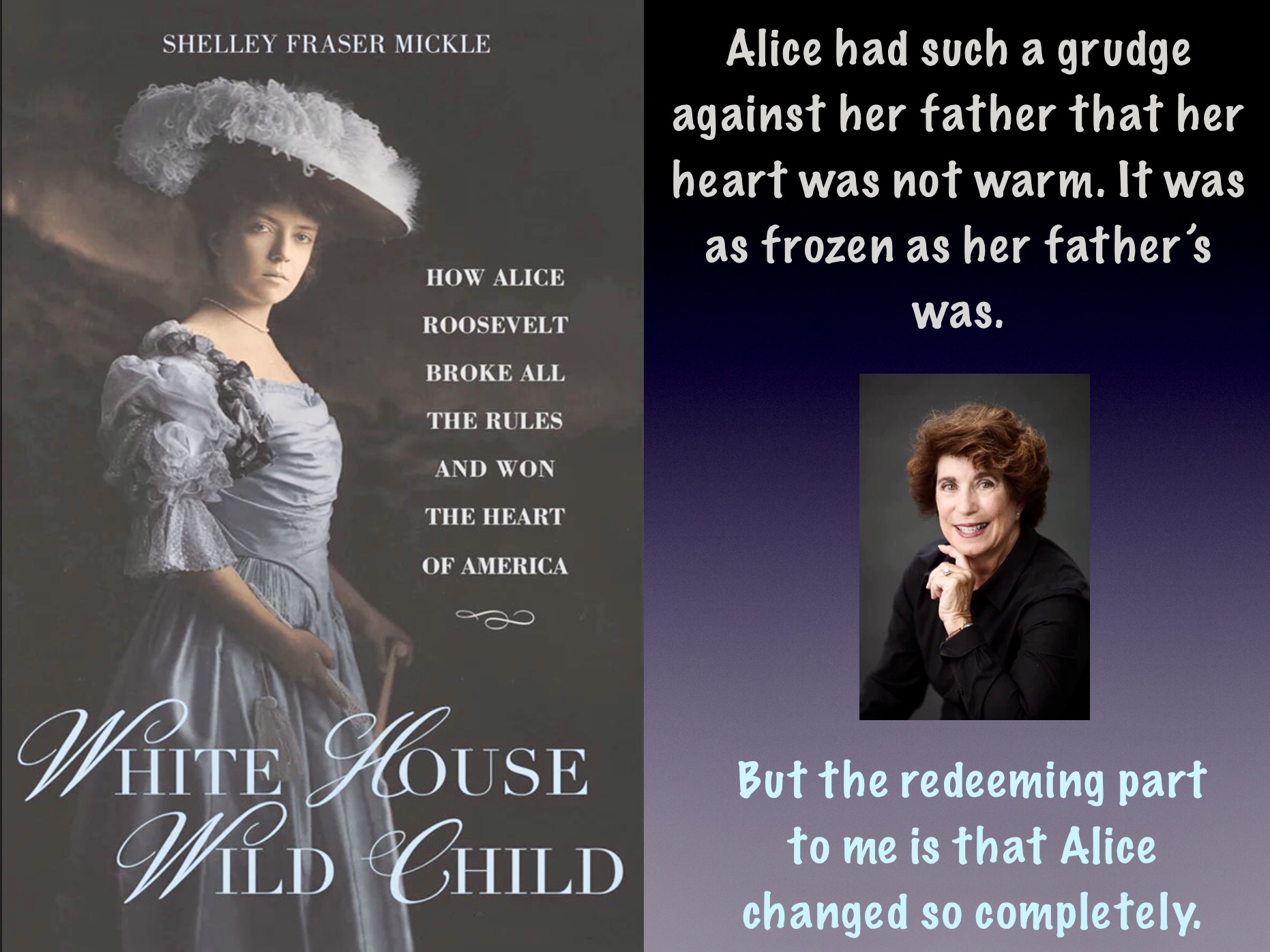

Mickle’s latest book, “White House Wild Child: How Alice Roosevelt Broke All The Rules And Won The Heart Of America,” is a meticulously researched account of the celebrated Roosevelt dynasty rebel who was dubbed “Princess Alice” by the press and would become the most photographed woman of her era.

Known for her sharp tongue and progressive ideas – neither of which endeared Alice to her President father – she was Gloria Steinem “before there was Gloria Steinem.”

But she was also very much a tragic figure.

“Alice had such a grudge against her father that her heart was not warm. It was as frozen as her father’s was,” Mickle said.

T.R.’s first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee, died just two days after giving birth to Alice. And her sudden loss left Roosevelt so grief-stricken that he couldn’t bring himself to utter his child’s given name – he called her “Baby Lee” – let alone show Alice much by way of fatherly affection.

Alice was sent off to live with her aunt, Anna “Bamie” Roosevelt, for the first three years of her life while T.R. fled to his ranches out west, taking to extremes the roles of grieving widower and absentee father.

Ironically, it was the circumstances of Alice Lee’s death that set Mickle on a circuitous path to writing “Wild Child.”

Mickle’s previous non-fiction book, “Borrowing Life,” was an account of the scientists who pioneered transplant surgery, beginning with the first successful kidney transplants. That book “led me to realize how many historical figures suffered from kidney disease, including Alice’s mother” who died of renal failure.”

“I thought ‘Wow! What a great novel that would be.’”

But Mickle had put fiction writing behind her.

“I started researching Alice and went on from there,” she said. “I did not really have the credentials” to be a biographer. And I had written so much fiction that I knew I had to be very careful” to tell Alice’s story correctly.

But make no mistake. Mickle put her well honed novelist skills to good use by turning what might otherwise have been an accurate if dry historical accounting into almost lyrical prose about a young woman who took life on her own terms and to hell with the consequences.

There is much interpretation – call it reading between the lines – in “Wild Child.” As when Mickle writes, “Deep down, she longed for his approval more than any other longing in her young life…(it)…was the holy grail that drove her.”

“I think my strength, from having written novels, is that I understand narrative drive,” she said. “My job as historian is to interpret history. But so many biographies are dry. My job was to make it into the story that gives the readers an understanding of what happened and why.”

To be sure, the father-daughter relationship that lies at the heart of “Wild Child” was a complicated one.

It is a measure of President Roosevelt’s regard for Alice’s political acumen that he sent her to tour the Orient in order to distract the press as his delegate, William Howard Taft, quietly negotiated a settlement to the Russo-Japanese war. The press dubbed the tour “Alice in Wonderland.”

But it is equally a measure of Roosevelt’s inability to connect with Alice on a familial level that, in his book “Letters To His Children,” T.R. “did not include any of his letters to her.”

Ultimately that father-daughter emotional turbulence would have tragic consequences for Alice and her own daughter.

Relatively late in life, Alice had a child with an older man, not her husband, who could have been a T.R. clone.

Lacking her famous mother’s verve and grit, Paulina Longworth was a sickly child and a withdrawn adult. She died of a sleeping pill overdose at the age of 31.

After her death, Alice fought for and won custody of Paulina’s daughter, Joanna. And Alice devoted herself to being the kind of mother she never was to Paulina.

“I think it’s a truism that we tend to repeat the family dynamics we have grown up with,” Mickle said. “But the redeeming part to me is that Alice changed so completely” after her daughter’s death. “It was grief that did it. The same grief that changed her father so profoundly.”

“I’m so proud of being able to distill history for readers to know the real Alice not just her antics.”